Sea Forests

Jennifer Adler

Underwater forests line almost one-third of coastlines worldwide. Thriving in temperate, nutrient-rich waters, these kelp forests are coral reefs forgotten cold water cousins.

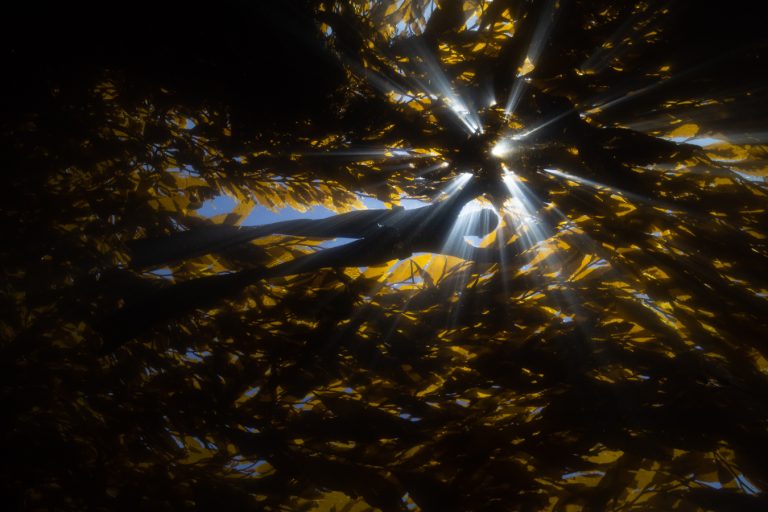

I spent the past 3 years documenting kelp forests on 4 continents, first at home in California and North America, then across the Pacific in Japan and south to Australia and Antarctica. Kelp are algae: they sequester carbon, buffer coasts from waves and storm surge, and provide the base for incredible underwater ecosystems. When sun shines through the golden canopy, diving in the kelp rivals a hike in the redwoods, but underwater, you’re weightless.

Scientists estimate 40-50% of kelp forests have disappeared worldwide, largely due to climate change and trophic cascades. Through my work, I hope to illuminate what we can learn from different kelp restoration and conservation efforts that may help us protect or better study kelp forests worldwide. In Baja and Japan, I documented the power of community-based conservation with the fisheries cooperatives and ama divers. In California and Australia, I photographed scientists studying the kelp. And in the sub-Antarctic islands of South Georgia and the Falkland Islands, I found some of the last untouched, towering kelp forests below snowy peaks where Shackleton once sailed.

Kelp forests may be invisible from shore, but they are vital to life, both human life on land and the abundance of species that depend on them underwater. They link us across cultures; a dive in the kelp becomes a common language, no matter the country or continent.

North America

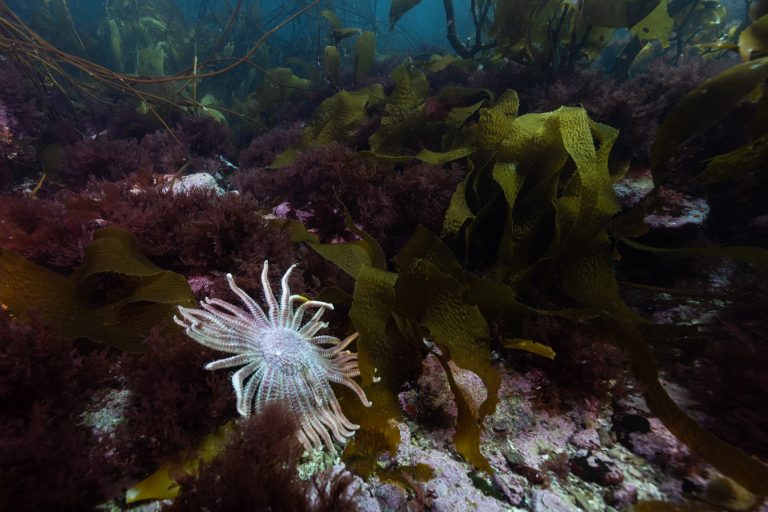

Kelp forests line almost the entire west coast of North America, from the Aleutians to Baja California Sur. Near extirpation of sea otters, combined with sea star wasting disease (SSWD), caused an explosion of their prey, purple sea urchins, which eat kelp. Large-scale urchin barrens now dominate where there were once flourishing kelp forests. Notably, northern California lost 90% of its bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana) in 2014, and there has been a range contraction at the southernmost extent of giant kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera) in Baja California Sur, which is predicted to worsen with increasing sea temperatures. I spent two years working with scientists from Alaska, California, and Mexico to understand how these kelp forests are changing and what people are doing to restore them.

Antarctic

Kelps grow along coastlines on every continent except Antarctica, yet the sub-Antarctic islands of South Georgia and the Falklands host towering forests in near-freezing water—the southernmost kelp forests on Earth. Remarkably, it is the same species, Macrocystis pyrifera, that I swim with at home in Monterey, California. There, we dive among the northernmost stands of this kelp; here, it reaches the furthest extent of its southern range, rising beneath snow-covered peaks.

While kelp is disappearing in California, it thrives in these polar waters. During our dives in the early Southern Hemisphere summer, temperatures hovered between 0 and 2°C. With minimal warming and limited human impact, these islands offer a rare glimpse of intact, ancient kelp forests—true “redwoods of the sea.”

Japan

Japan’s oceans are global biodiversity hotspots, home to 38 species of kelp. But coastal Japan lost 30% of its seaweed beds in the 1990s. Sea surface temperatures around Japan have risen twice as quickly as oceans worldwide, which has profound impacts on kelp forests. Temperate kelps such as Ecklonia cava have experienced the sharpest declines. This loss of kelp, known as “barren ground phenomenon” or isoyake, is expected to become more frequent and severe with continued ocean warming.

Japan’s ama divers have been freediving for more than 2,000 years. Kelp forests are significantly important to these ama fishers because kelp is the primary food source of abalone, their most valuable catch. Despite careful community-based management in fishing cooperatives, landings of prized abalone have severely declined as kelp forests have disappeared. In 2023, we visited Japan to explore how climate change threatens the remaining ama divers and kelp forests and revisited places that National Geographic photographer Luis Marden photographed for his 1971 Magazine feature. We found several of the same ama divers still diving 50 years later.

Australia

Giant kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera) forests along Tasmania’s coast have declined by 95% in recent decades, largely due to ocean warming and the growing influence of the warm, nutrient-poor East Australian Current (EAC). These two climate-driven forces have caused the waters of Southeast Australia to warm at nearly four times the global average, making the region a global ocean-warming hotspot.

In 2012, these kelp forests were the first marine community in Australia to be listed as a Threatened Ecological Community under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act. As in North America and Japan, sea urchins (Centrostephanus rodgersii) are also exacerbating kelp losses here as the warmer current facilitates the sea urchin’s range-expansion into the Tasman kelp forests. Because warming is such a problem for the kelp forests here, scientists from the University Tasmania’s Institute of Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS) of have been working to ‘future proof’ the kelp by selecting and planting warm-tolerant Macrocystis ‘super kelps.’